History of the Colorado Chautauqua

In the late 1890s, a group of Texans (including University of Texas president G. F. Winston) wanted to open up their own Chautauqua and looked to the Rocky Mountains for a location. Boulder was chosen for the site of Chautauqua and Boulder citizens, thrilled to have a Chautauqua nearby, raised $20,000 towards construction costs. The city of Boulder purchased 171 acres from the Bachelder Ranch and the Austin-Russel tract for the new Chautauqua, the first purchase of private property by the city of Boulder. The Texans covered expenses of running the Chautauqua programs.

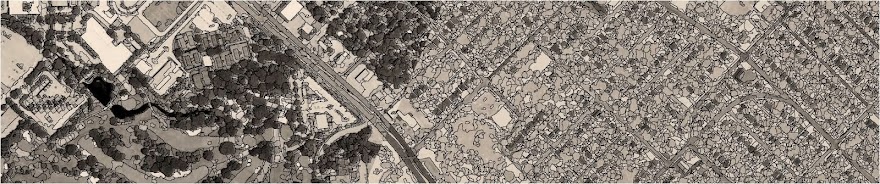

|

| "The First Chautauqua at Boulder, Colo. 1898. Texas-Colorado Chautauqua, looking west. H. F. Pierson photo, Denver, Colo." Boulder Carnegie Library for Local History, 511-3-9 PHOTO 1. |

The Colorado Chautauqua was part of the national Chautauqua movement, which was nationally known for its emphasis on intellectual pursuits, moral self-improvement, and civic involvement. The movement began in upstate New York in 1876 as a center for political, educational, and recreational programs. By 1924, nearly 40 million people were annually attending events at over 300 Chautauquas across the country. The Chautauqua movement died out by the mid-1930s. Most historians cite the rise of car culture, radio, and movies among the primary causes as well as social changes, including a sharp increase in fundamentalism and evangelical Christianity in the 1920s, alternative educational opportunities for women, and the economic impossibility of organizing programs. Many Chautauqua communities became camp meetings or church camps.

By 1955, Boulder's Chautauqua was one of only six remaining in the country. The programs and activities continued at the Colorado Chautauqua as they had since the beginning, but many of the building began to deteriorate. By 1975, the city of Boulder considered tearing the buildings down, but concern about the future of the park inspired the citizens of Boulder and the Colorado Chautauqua Association to implement a program to preserve the park and its historic buildings, structures, and landscape. In 1978, Colorado Chautauqua was designated as a local historic district and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2006, Colorado Chautauqua was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Managing the Viewshed of the Colorado Chautauqua

Recently, Open Space and Mountain Parks Department (land managers for Chautauqua Meadow and lands surrounding Colorado Chautauqua) proposed repairs to the Chautauqua Trail. Chautauqua Trail is the flagship trail that most visitors (over 3 million annually) hike during their visit to Chautauqua Meadow or Colorado Chautauqua. The current trail design is problematic and leads visitors to hike off trail, causing braiding, erosion, and expansion of the trail corridor. The trail was maintained to be 8 feet wide; it is currently 24 feet wide in spots (Figure 1). Additionally, there are several informal gathering areas where folks like to take photos with the Flatirons in the background. Open Space and Mountain Parks would like to improve the trail by stabilizing the trail tread and to designate low development level gathering areas to minimize existing resource damage.

|

| Figure 1. Photo CT.7785: Overview of Chautauqua Trail below/northeast of Gathering Area 2 (GA2) looking northeast towards Colorado Chautauqua. Braiding, gullying, weed encroachment visible on trail. |

1. 3D Viewshed Model

I constructed 3D viewshed models with ArcGIS 10.4 of the lines of sight from our treatment locations (Figure 2), key observation points identified by the stakeholder (Figure 3), and key observation points identified by Open Space and Mountain Parks (Figure 4). These locations are listed below. The viewshed models were generated using a 1 foot spatial resolution digital surface model (DSM) that included obstacles (buildings, vegetation). The DSM was derived from post-flood aerial LiDAR point cloud for the City of Boulder. The height of the observer was chosen at 6 feet above ground surface, simulating the viewshed for taller individuals to maximize the visibility of surrounding features.

Creating 3D viewsheds in a geographic information system (GIS) have benefits and drawbacks compared to other methods of viewshed assessment. A GIS is better able to consider the effects of terrain relief and curvature of the earth, creating a quantifiable output of what areas are visible or not from a given location. Because of Earth's curvature, lines of sight can only extend up to 3 miles or 5 kilometers unless drastic changes in elevation are involved. A GIS makes it easier to assess object and observer heights. Our models did not consider atmospheric refraction and how visibility of an object is affected. The GIS models also do not address observer's visual acuity. An object may have a clear line of sight to an observer, but an observer may not have the ability to see that object.

Visualizations from the model illustrate the results. The viewshed model for our proposed treatment locations shows that little of the landmark shares clear lines of sight with the treatment locations (Figure 2). The viewshed from Colorado Chautauqua is not substantially impacted (Figure 3). In assessing the potential for adverse indirect effects of our proposed treatments, we expect that no areas of concern at Colorado Chautauqua showed potential for adverse effects. The viewshed towards Colorado Chautauqua from the Chautauqua Meadow is likely to be impacted by the proposed treatments (Figure 4). There are clear lines of sight from one key observation point at each gathering area.

|

| Figure 3: Lines of sight from stakeholder-identified key observation points. Cells are color coded for how many key observation points have clear lines of sight to them. |

|

| Figure 4: Lines of sight from Open Space and Mountain Parks-identified key observation points. Cells are color coded for how many key observation points have clear lines of sight to them. |

_________________________________________________________________________________

DESCRIPTIONS OF KEY OBSERVATION POINTS:

| CCA1: | Vehicle entry at Kinikinik Road | OSMP1: | 7th Street and Baseline | GA1: | Gathering Area 1 | ||

| CCA2: | Chautauqua Green | OSMP2: | Divergence of Baseline and Flagstaff Road | GA2: | Gathering Area 2 | ||

| CCA3: | Gwenthean Cottage | OSMP3: | Armstrong Bridge | ||||

| CCA4: | Chautauqua Arbor | OSMP4: | Ski Jump Trail at woodland edge | ||||

| CCA5: | Bluebell Road (Cottage 26) | OSMP5: | Chautauqua Trail and Bluebell Mesa Trail | ||||

| CCA6: | Columbine Lodge (west hallway on 2nd floor) | OSMP6: | Bluebell Mesa Trail at woodland edge | ||||

| CCA7: | Columbine Lodge (northern elevation porch on 2nd floor) | OSMP7: | Bluebell Road (near Cottage 811) | ||||

| CCA8: | Cottage 16 | OSMP8: | Meadow Trail near Civilian Conservation Corps site |

2. Visual Contrast Rating Survey

|

| Figure 6: Triangular 12 inches by 6 inches target. Targets were placed in proposed gathering areas. |

|

| Figure 7: Subset of VCR survey group, including OSMP trail project manager, archaeologist, and Colorado Chautauqua Association Facilities Manager |

The VCR methods holds that degree to which a management activity/treatment affects the visual quality of a landscape depends on the visual contrast created between a project and the existing landscape. The contrast can be measured by comparing the project features with the major features in the existing landscape. The basic design elements of form, line, color, and texture are used to make this comparison and to describe the visual contrast created by the project.

A VCR survey was completed in two days by four people, including a representative from the concerned stakeholder. Data and findings are still being compiled from the inventory forms. Discussions during the survey found consensus in how few of the treatment areas were actually visible by our own sight from key observation points.

Consultation for this project is still ongoing with 30% Plan Sheets anticipated to be released in the next few weeks. I will update this post periodically as we advance in the planning process, particularly as we may need to seek additional clearances with a local landmark board to proceed. This viewshed analysis and visual resource assessment provided robust framework for conversations about indirect effects to significant historic properties. I consider this process successful in achieving our goals.